A mechanical watch is a true work of miniature engineering, regardless of the expense. A sub-€300 Seiko 5 Sports has the same basic mechanical elements and wonder as a four-figure IWC, and is just a bit less detailed and accurate day-to-day. Almost self-sufficient and independent of electricity, a mechanical watch simply needs to be wound to maintain a constant state of motion. Feeding from the mainspring, the movement has a heartbeat and perhaps even a soul, but unlike a living organism, it’s comprised of metal gears, synthetic jewels, rubber gaskets, metal bearings and springs, and those need periodic maintenance like all complex machines. For example, your car engine would cease to operate if never serviced. Well, it’s the same with a mechanical watch, and here’s what you need to know about service and maintenance in our latest instalment of The ABCs of Time.

Starting From New

A new watch from either a dealer or direct from the watchmaker is expected to run for many years without issue. Problems within the first couple of years usually indicate a manufacturer’s defect and should be covered by a warranty. After a year of trouble-free use, most modern watches continue to run reliably and hassle-free for many more years. Internal friction and the rigours of daily wear do take a toll, however, along with inevitable deterioration of lubricating oils within the movement, so maintenance is needed at periodic intervals to keep things running optimally. This requires the opening of the case to work directly with the movement, no different than opening the hood of a car to work on the engine.

Who can do this work and the expense involved depends on the type of movement and manufacturer. A simple and proven ETA, Sellita, Miyota or Seiko movement, for example, can be serviced by most qualified watchmakers at your local repair centre, while complicated movements with in-house chronographs, tourbillons, perpetual calendars and so on require a more specialised watchmaker at a much higher price. In fact, the latter examples often necessitate work by the brand’s watchmakers themselves, meaning the shipment of a watch to Switzerland, Germany or wherever the atelier is based. Or, in the case of large brands like Rolex or Omega, official service centres with the right equipment to service more complex movements.

We’ve Come a Long Way with Jewels and Oils

Although there’s no such thing as a maintenance-free mechanical watch (yet), things are much better than in the old days. Following the invention of the lever escapement by Thomas Mudge in the mid-1700s, which is the escapement still used by most watches today, the general design and formula of a watch movement have remained the same. Maintenance needs varied wildly back then, largely based on the types of critical bearings used (metal or precious stones). Natural jewels were used to significantly reduce friction and wear as early as 1704 – rubies, sapphires, garnets and occasionally diamonds – and were expensive, hard to work with and quality from watch to watch varied.

Regardless, they all provided a much better wearing surface compared to brass counterparts with natural hardness and smooth, polished surfaces. From a maintenance standpoint, natural jewels were always superior and jewelled movements had longer service intervals and required fewer replacement parts over time. Unfortunately, natural jewels were a luxury for high-end watches and not available to the masses, so the average watch was maintenance-intensive by today’s standards.

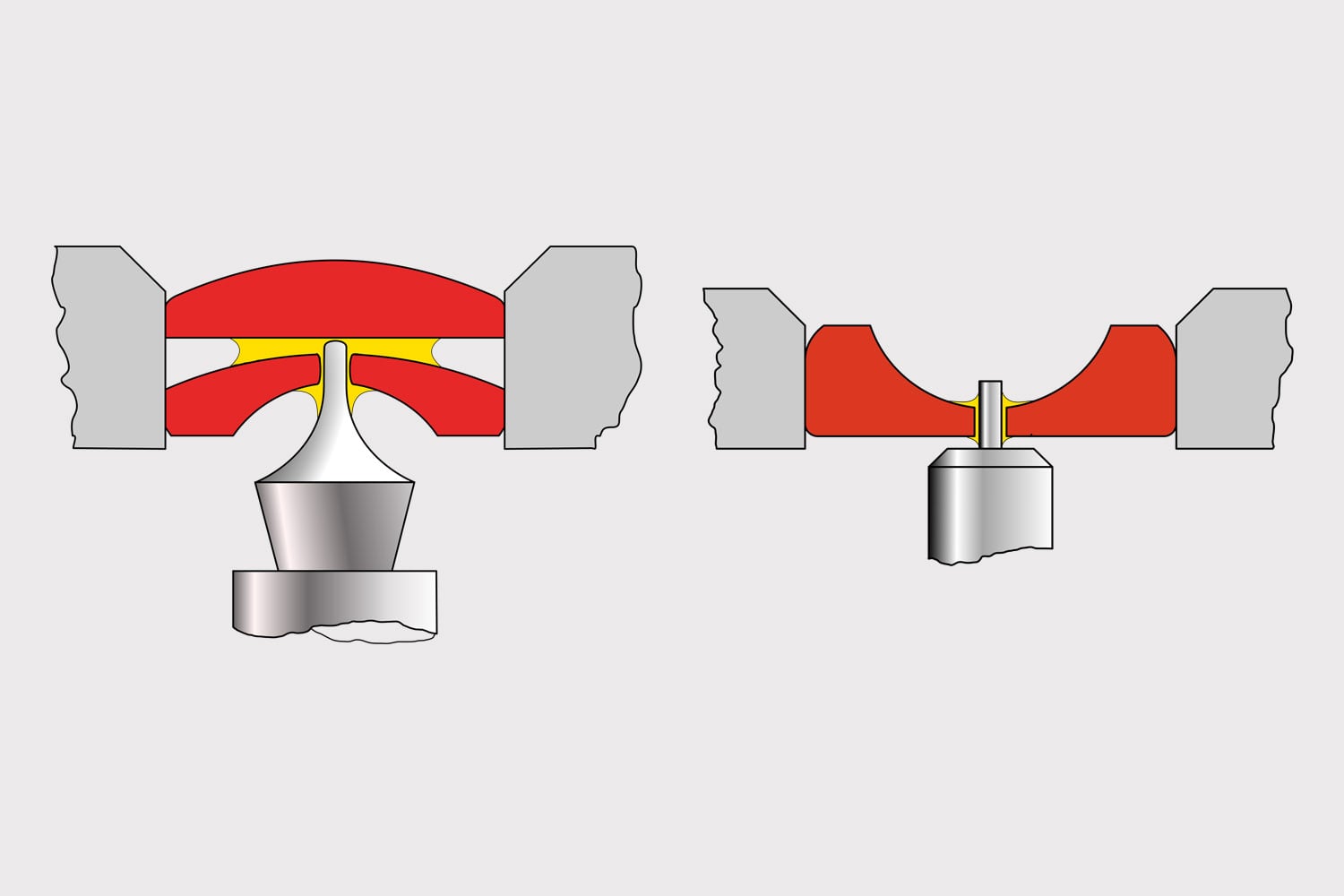

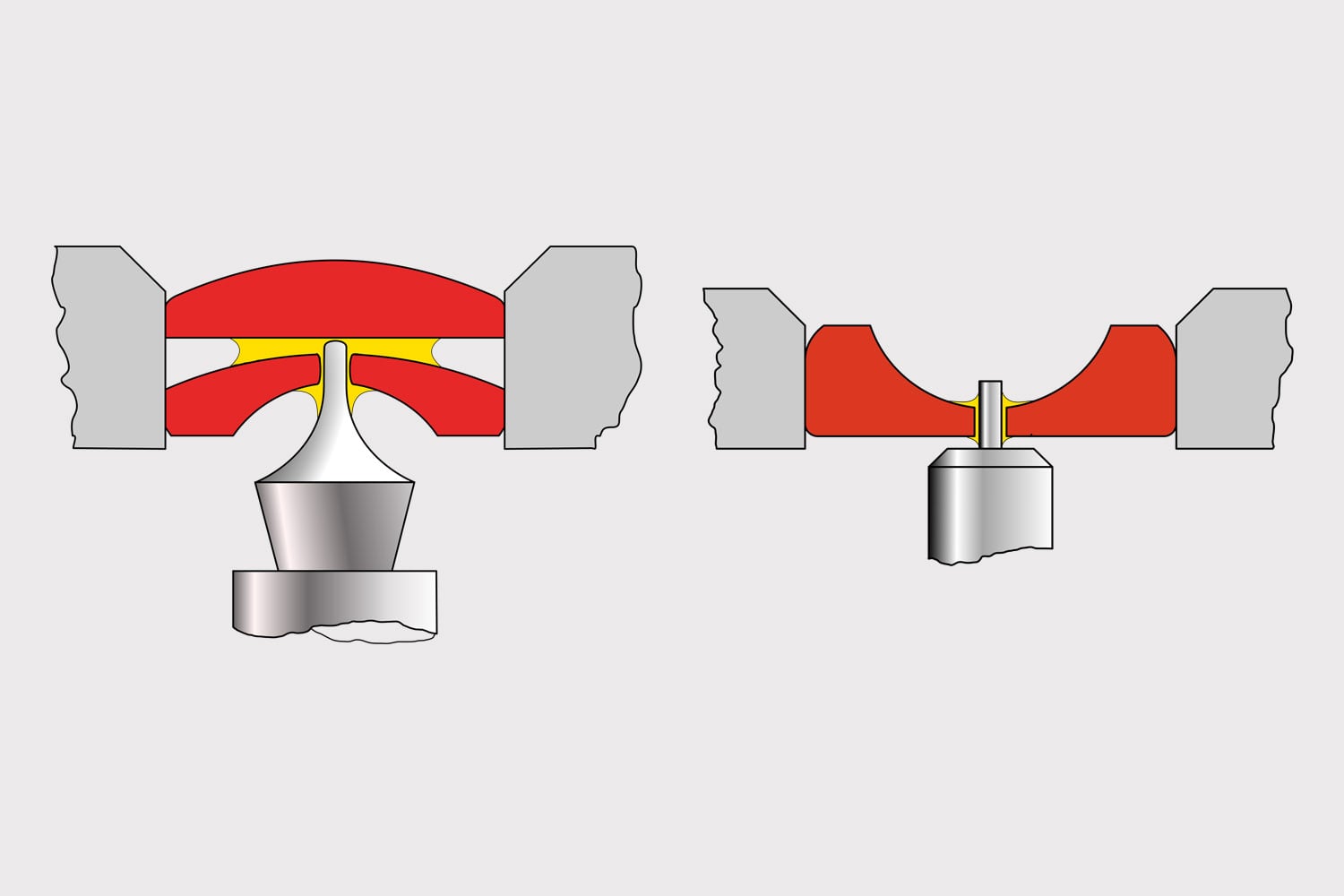

Cross-section of jewel bearings in mechanical watches

Cross-section of jewel bearings in mechanical watches

Synthetic jewels changed the game in 1902 when Auguste Verneuil invented the process to make corundum – synthetic sapphires and rubies for watches (the same process is used for sapphire crystals). Synthetic rubies have actually been around since 1837, but Verneuil’s flame fusion process allowed for production at scale for watchmaking. Synthetic jewels are just as hard and wear-resistant as natural counterparts (9 on the Mohs hardness scale), but aren’t considered expensive precious stones and have revolutionised the longevity and reliability of watch movements. They’re also used at the tips of most escapement pallet forks, reducing friction and wear as they interact with the escape wheel teeth (creating the tick-tock sound of a watch).

Lubricating Oils

Although the jewel bearing was generally the final piece of the puzzle for optimised watch movement design, lubricating oils played an equally important role. Historically, they’re natural lubricants like neatsfoot oil made from the fats of cattle. Sperm whale oil was also used, which was better than cattle-derived oil, but rarer and more expensive. All-natural watch oils had a common theme – they’d thicken over a relatively short time period and gum up moving parts, and could deteriorate within a matter of months. Watch movements needed to be carefully cleaned and lubricated fairly frequently, which was acceptable back in the day, but wouldn’t be so tolerated today.

Like synthetic jewels, synthetic watch oils were a game-changer and became widespread in the 1950s. They proved resistant to thickening and stickiness over time and generally lasted for many years without deterioration. It was so good, in fact, that many watchmakers initially shunned the new development as it greatly reduced the need for watch maintenance and the revenue that it generated. Synt-a-Lube 9010 is an example of a popular synthetic watch oil made by the Swiss company Moebius (Moebius 9000 oil is used for quartz watches), and virtually all modern mechanical watches use both synthetic jewels and oils for reliability and longevity.

Silicon Parts

In 2001, Ulysse Nardin became the first major watchmaker to use silicon components for its Freak model, starting with the hairspring and escape wheel. Many high-end brands followed, including Patek Philippe, Swatch Group and Rolex, and silicon is now somewhat common in mainstream watches from Swatch Group, notably in some ETA’s Powermatic 80 calibres. The advantage of silicon is its incredible wear resistance and minimal need for oil (if any), resistance to magnetism and corrosion, and high resistance to temperature fluctuations. From a maintenance standpoint, it’s far superior to conventional metals, thereby extending service intervals. The most common use today is for escapements and hairsprings, such as in all of Omega’s movements and Rolex’s calibre 7135 in the new Land-Dweller with a silicon double-wheel Dynapulse escapement. Sigatec (among others) is a major Swiss manufacturer of silicon for watchmaking and also smartphones, as the material is historically known for computer chips.

![]()

![]()

Experiments with oil-free nanotech coatings for escapements and other components could eventually eliminate the need for oils and reduce component wear to near zero, and a combination of nanotechnology and silicon in watch movements could make service intervals a thing of the past. Imagine a watch that reliably ticks for generations without maintenance.

Back to the Reality… Periodic maintenance

Unfortunately, we still need to maintain/service our mechanical movements today, as oils, at the very least, eventually need to be replaced. Even the best synthetic watch oils break down over time due to dust and humidity, just like synthetic oils in your car (they last longer than conventional oil, but not forever). So, what exactly is involved during a service?

For a general service involving a simple, common mechanical movement, a local watchmaker will open the caseback and remove the movement. It’s then disassembled, and parts are cleaned in an ultrasonic bath to remove oil residue and other possible contaminants. Parts are carefully inspected for wear and damage, and anything that’s worn out or damaged (gears, arbours, etc.) will be replaced to restore the movement to its original specifications. When all parts meet the watchmaker’s approval, the movement is oiled during reassembly and then regulated/adjusted to ensure specified accuracy.

This usually involves adjusting the length of the hairspring in tiny increments with an integrated lever or screw, which fine-tunes the balance wheel’s oscillation. The dial and hands are often inspected, along with the case and bracelet/strap. The customer decides whether a cosmetic overhaul is desired, such as polishing the case, replacing the hands, or replacing a cracked/faded dial. Most modern watches have a water-resistance rating, so gaskets at the crown and caseback are also replaced, and water-resistance is usually tested (particularly for dive watches).

As you can see, a general service is fairly intensive, requiring a skilled watchmaker, specialised tools and time, but more complicated movements often need to be serviced by the brand itself to ensure the right parts, tools and know-how. Servicing a tourbillon, perpetual calendar, or chiming watch is much more time-consuming than servicing a simple time-and-date movement, and prices consequently rise significantly. A Patek Philippe perpetual calendar could easily run north of EUR 2,000 for a service, while a common ETA, Sellita or Miyota can be as little as EUR 150 at a local watchmaker.

A fully equipped Rolex service centre – like servicing your car at a manufacturer’s official dealer, such maintenance comes at a cost, but very often with an elongated warranty

A fully equipped Rolex service centre – like servicing your car at a manufacturer’s official dealer, such maintenance comes at a cost, but very often with an elongated warranty

High-end brands tend to be more expensive in general, particularly if watches are sent back to headquarters or an official service centre. A time-only Rolex movement, such as calibre 3230 in the Explorer, could run EUR 700 for a general service, while a time-only Audemars Piguet Royal Oak could be double or even triple that price. It’s usually less expensive if an experienced local watchmaker performs the service rather than the brand itself, but they’re not always easy to find. And, with brands implementing more and more proprietary technical solutions (Dynapulse, Co-Axial, Spring-Drive and more), a non-affiliated watchmaker will sometimes have a hard time servicing a watch, due to the lack of the necessary tools and parts.

Luxury brands also tend to be motivated to restore dials, cases, hands, and so on to a near-perfect condition during a service, which can significantly increase the price. For example, my cousin has a 1980s Rolex Datejust that needs service and repair, as the crown won’t wind the movement (but the automatic rotor winds it without issue). Rolex wants to replace the dial, hands, crystal, bezel, Jubilee bracelet and even the case to restore it to factory specifications, and quoted over USD 4,000. My recommendation is to have an experienced local watchmaker service the movement, repair the crown/stem and replace the crystal, leaving the rest in original condition as it’s cosmetically sound overall. That would come to around USD 1,000, which is a significant price difference. Of course, it’s up to you how far you want to go, and if he let Rolex service the watch as originally intended, it would look and function like a brand new Datejust.

How Often Does This Need to be Done?

Service intervals vary from watch to watch, and components like silicon can extend the time between services. As a rule of thumb, a service should be done every five years, although many enthusiasts recommend holding off if the watch runs well and remains accurate. Some high-end brands have much better service intervals today than even the recent past – Rolex recommends a service every 10 years, for example, while an accessible brand like Hamilton recommends three to five years. That said, Vacheron Constantin, one of the most elite brands and a member of the Holy Trinity, recommends no more than five years as well. I have friends who go well beyond 10 years between services with very expensive watches, and many simply wait for accuracy issues, etc., before incurring the expense and inconvenience.

I fall somewhere between factory guidelines and “waiting until something breaks” to get my watches serviced. If a brand recommends up to five years, I’ll check if accuracy has changed in year five and then make a decision. If all is well, I’ll hold off for another year or two for a service, but I also won’t simply wait for something to go wrong. Servicing a movement is vital for longevity, and a well-maintained watch can literally last for over a century. I’ve handled original pocket watches from the 1700s that keep surprisingly accurate time, while I’ve also seen neglected watches from the late 1990s stop running altogether.

We live in an age where mechanical watches are basically obsolete, and an owner chooses to wear one despite time always being in our pockets with smartphones (and all around us with computers, tablets, digital car screens and so on). It’s more of a passion today than a necessary tool of the past, so servicing tends to be neglected. There’s certainly an inconvenience and expense involved, but always service your watch (especially high-end pieces) to ensure proper function, accuracy and longevity, and it could be passed down for generations.

https://monochrome-watches.com/the-abcs-of-time-the-basics-of-mechanical-watch-maintenance/